The trouble with freedom these days is not that we have too little of it, but that we have forgotten what it is made of. We shout the word as if volume were virtue; we wield it like a weapon, swing it in wide arcs, and then wonder why we keep hitting each other in the face. Somewhere in all our noise, the old idea has slipped away — the quiet, difficult, grown-up notion that liberty is not a feeling but a practice.

A thing you do, not a thing you demand.

I do not write these letters because I imagine myself wiser than my neighbors. Grammina used to say that a man who thinks he’s the only adult in the room probably isn’t one. No — I write because I see in myself the same passions, the same quickness of instinct and appetite, that the Founders saw in themselves. They knew human beings well enough not to trust us with easy power, and they knew freedom well enough not to confuse it with indulgence. We forget this, and forgetting is how republics waste themselves.

Let’s speak a truth plainly, even if it’s uncomfortable:

Our republic began with a sin so large it could not help but deform the nation that inherited it.

Slavery cracked the foundation before the mortar had even dried. The very people who wrote that all men are created equal allowed a system in which that equality was denied by law. We still carry the fracture. We still speak in the poisonous vocabulary of domination — of winning and owning and punishing — because we were raised inside a nation that had to teach itself equality backwards, against its own shadow.

But the fact that the Founders failed to fully live their creed does not make the creed false. It makes it urgent.

“All are created equal” is not just a sentiment. It’s a design principle.

It tells us that no person — not the majority, not the minority, not the loud, not the mighty — has the right to interfere in anothers life any more than that person has the right to interfere in theirs, nor to dictate the inner life of another soul. Freedom is the space in which one may act without depriving another of the same space.

Freedom is mutual, not solitary.

And that is where we have lost our way.

Too many Americans speak of liberty as if it were a private inheritance, something they may spend however they choose regardless of the cost to others. But liberty is not a solitary possession; it is a shared condition. If your freedom depends on diminishing mine, it is no longer freedom — it is just a polite word for dominance.

Jefferson warned of this,

Madison designed a government to restrain it…

because they had studied enough history to know that majorities are no more virtuous than kings.

Which brings us to democracy.

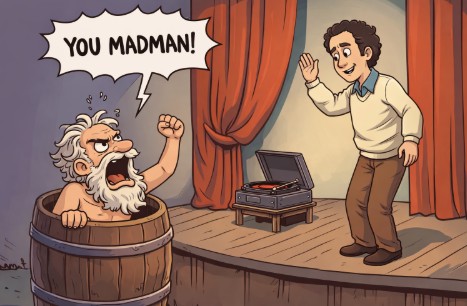

Or, more precisely, to the modern confusion that democracy is an end in itself. It is not. Democracy is passion with a headcount. Left unchecked, it becomes a contest of appetites, a brawl in which whoever yells loudest mistakes themselves for righteous. The Founders feared this — not because they distrusted the people, but because they were the people and knew their own weaknesses.

A republic, by contrast, is democracy with brakes.

It slows us down.

It forces reflection.

It requires coalitions.

It protects the individual — the one, not the many — from the passions of the moment.

And here is the neglected truth: the government’s purpose is not to indulge our instincts, but to protect us from them. Mine from yours, and yours from mine.

The same holds in matters of conscience.

We talk as if freedom of religion exists to protect only believers, or only non-believers, depending on the decade. But Madison — that thin, frail apostle of reason — insisted that conscience is the first freedom because thought cannot be coerced, and attempting to do so only distorts the soul.

The Quakers, for their part, held that the Inner Light needs no enforcer. Truth, being truth, need not fear error; error, being error, cannot be defeated by force. Enlightenment is discovered, not demanded.

If we remembered that, our public disputes would be a good deal less violent.

So this is my small plea in a loud age:

Let us recover the idea that freedom requires restraint — not the imposed restraint of tyrants, but the chosen restraint of adults.

Let us retire the language of domination we inherited from our original sin and learn again to speak in the tongue of the eighteenth century: the language of natural equality, of reciprocal liberty, of self-governance.

Because a free society is not built by the people who demand the widest swing of their own arm; it is built by those who stop just short of another’s nose, and do so not because they are forced, but because they understand that the other nose belongs to someone equally free.

If we can remember that, the republic may yet remember itself.

Closing Grace:

“Freedom is the distance between desire and discipline.”

-N