A proposal to turn blighted malls into rescue colonies, living archives, and a non-invasive research platform for animal intelligence

America has a growing inventory of empty commercial space: abandoned strip malls, shuttered big-box stores, and full indoor malls that have become dead zones in the middle of otherwise living cities. These buildings are often structurally sound, already served by utilities, and large enough to host complex, layered environments—yet they sit underused because the old retail model no longer fits.

At the same time, cities and towns everywhere struggle with a different problem that rarely gets framed as infrastructure: cats. Feral colonies, strays, overwhelmed shelters, and rescue networks doing heroic work with limited resources. And beneath that practical issue is a deeper one: domestic cats are an intelligent, socially flexible species living in human environments that constantly erase the information cats naturally create to stabilize their world.

This article proposes an experiment and a business model that addresses both problems at once:

Convert blighted malls into a “Feline Commons”: a layered, indoor rescue colony where cats live safely, visitors fund operations, adoptions happen by cat choice, and researchers study cat cognition and social behavior through observation—without invasive procedures, coercion, or harm.

This isn’t a petting zoo. It isn’t a traditional shelter. It’s a new category of urban reuse: a living system designed around feline behavior and long-term environmental memory.

The core idea: cats leave “writing,” and we keep wiping it away

Cats do not rely on speech to coordinate their lives. They rely on durable marks and cues:

- Scratching and shredding (visual + tactile persistence)

- Rubbing (facial pheromones; familiarity and “safe ownership”)

- Spraying in some cases (high-salience boundary or stress signaling)

- Repeated traffic paths and preferred perches (spatial norms)

- Layered scent on shared structures (community continuity)

In the wild, these signals accumulate on trees, rocks, paths, and favored resting spots. In modern domestic life, humans constantly erase them:

- We throw out old cat trees because they look worn

- We deep-clean areas cats repeatedly mark

- We rearrange rooms and remove objects that hold familiar scent layers

- We replace “used” structures rather than letting them persist

To a cat, this is not just redecorating. It is repeated removal of stored information—an ongoing demolition of familiar landmarks.

A blighted mall, however, offers something few homes can: space stable enough to retain history.

The hypothesis: can stable environmental markers produce “cultural assimilation” in cats?

The experiment is grounded in a straightforward, testable question:

If cats live in a stable environment where scratch and scent markers persist over time, will new cats assimilate more quickly and more peacefully into the colony than they would in typical shelter environments?

This matters because most rescue contexts are the opposite of stable: frequent cleaning, frequent rearrangement, frequent turnover, and high stress. Those settings save lives—but they may unintentionally make social integration harder.

The “Feline Commons” setting does the reverse:

- It preserves environmental memory

- It allows cats to self-organize

- It supports multiple social styles (reclusive, transitional, social)

- It allows long-term patterns to emerge

The key claim is not that cats develop human-like language or art. The claim is that they may develop place-based norms—a persistent, shared “how things work here”—encoded through markings, routes, and repeated use.

If that’s true, then a new cat entering a marked environment is not starting from zero. It is entering a system that already contains information.

The facility: a layered feline district inside a mall

A full, dead mall is ideal because it naturally provides:

- Multiple corridors and sightlines

- Vertical routes (stairs, escalator voids, mezzanines)

- Separate zones that can be isolated without feeling like cages

- Long-term stability (anchors can remain in place for years)

- Utilities, parking, loading docks, and public access geometry

The three-layer layout (the ethical core)

This is not a filter that “fails” reclusive cats. The system is designed so every temperament has a place.

Layer 1: Deep Retreat Zones (cats-only)

- No public access

- Low noise and controlled lighting

- Dense cover, many hiding structures, high perches

- Minimal staff intrusion (care is efficient and calm)

- Stable placement of key “legacy” structures

Purpose:

- Provide safety for feral, traumatized, or low-contact cats

- Allow recovery without pressure to perform socially

- Preserve environmental continuity

Layer 2: Transitional Zones (low-contact)

- Limited, slow human presence (staff, researchers, controlled tours)

- Cats can observe humans without being approached

- Elevated cat-only pathways allow movement without human interaction

- Multiple escape routes and low conflict bottlenecks

Purpose:

- The main “learning” layer for both cats and observers

- Where cats test boundaries and move toward or away from contact on their own terms

Layer 3: Social Interface Zones (public-facing)

- Cafés, lounges, galleries, small boutiques

- Quiet rules enforced (no chasing, no forced touching)

- Cats choose whether to enter and interact

- Humans are guests, not handlers

Purpose:

- Generates revenue

- Allows voluntary human-cat relationships to form

- Supports adoption by cat preference

This layered model makes the project defensible: cats are never forced into human space, and humans never “extract” interaction.

The “legacy artifact” system: cat trees as history carriers

A central feature of the experiment is the use of donated cat trees and marked structures from around the country.

How it works

- Cat trees are donated from households, rescues, and shelters

- They are re-skinned with fresh carpet/sisal/rope or covered with replaceable layers

- The goal is to refresh the surface while retaining deeper scent and “use memory”

- These structures are placed as stable anchors across the building

This creates a substrate where:

- marks can accumulate across time

- the environment becomes “readable”

- the colony develops persistent use patterns

- newcomers encounter a pre-marked world rather than a sterile reset

Whether or not regional “dialects” exist is an open question. But the environment can certainly develop local meaning: a structure becomes a landmark; a corridor becomes a known route; a perch becomes a social threshold.

Intake and care: rescue-first, research-second

This project only works if it is obviously, unambiguously beneficial to cats.

Intake

- Rescues and strays from the region

- Full veterinary assessment

- Spay/neuter

- Vaccination, parasite treatment, microchip, baseline health tracking

Infirmary

A dedicated on-site clinic is essential:

- quarantine rooms

- treatment and recovery wards

- isolation capability for outbreaks

- partnerships with local vets, vet schools, and nonprofits

Daily welfare principles

- Stable zones remain stable

- Cleaning is targeted, not sterilizing

- Public-facing areas can be cleaned thoroughly without erasing cat-only archives

- Nutrition and water distributed to avoid conflict points

- Enrichment that supports natural behaviors: climbing, hiding, patrolling, observation

This is not a high-turnover shelter model. It is a sanctuary with optional adoption.

Adoption model: adoption is an outcome, not the purpose

Most shelters operate on the logic of selection by humans. This model proposes something different:

Adoption happens when a cat reliably chooses a person.

Mechanism:

- Visitors can meet cats only through calm, passive presence

- Cats that repeatedly approach a specific visitor (over multiple visits) become candidates

- Staff confirms consistent behavior and suitability

- Adoption proceeds when the cat’s behavior indicates willingness

Some cats will never adopt. That is not failure. Those cats remain rescued and safe.

Research design: non-invasive observation that can actually answer questions

The research layer should be structured so it does not change the welfare-first mission.

What is studied

- Assimilation time for new cats (time to stable resting, time to normal eating, time to route formation)

- Social network formation (who shares space with whom; grooming clusters; conflict frequency)

- Space usage over time (preferred zones, corridor traffic, perch occupancy)

- Response to persistent markers (do cats treat heavily marked structures differently?)

- Long-term stability (do norms persist even as individual cats turn over?)

How it is studied

- Passive cameras in cat-only spaces (privacy protections for visitors)

- Volunteer observation logs

- RFID collars or non-invasive tracking (optional)

- Simple behavioral scoring (stress indicators, approach/avoidance, conflict events)

No forced tests. No deprivation. No invasive sampling as a default. The “experiment” is the environment itself.

The primary output is not lab papers. It’s knowledge that can improve rescue design everywhere:

- How to lower stress

- How to improve assimilation

- How to build shelters that function more like stable neighborhoods than holding facilities

The business model: tourism pays for rescue and research

The reason this can scale is simple: people already pay for cat experiences—often in small, cramped “cat cafes.” A full mall-scale sanctuary is something else entirely.

Revenue streams

- Timed-entry tickets (capacity capped for quiet)

- Café and food service (humans only; cats remain on separate feeding systems)

- Merch (ethical, rescue-supporting)

- Sponsorships from pet brands (with welfare requirements)

- Donations and memberships (“support a zone,” “sponsor a legacy tower”)

- Events: photography days, quiet lectures, adoption weekends, guided tours

- Grants: animal welfare, urban revitalization, non-invasive cognition research

Why malls are perfect for it

- Parking already exists

- Restrooms already exist

- HVAC can be maintained

- Multiple storefronts become cafés, clinics, staff rooms, galleries, observation lounges

- Security and access control are straightforward

In short: the exact features that made malls good for people make them good for managed, layered animal habitats—without the cruelty of cages.

The pitch to property developers: turn blight into a destination

A dead mall is expensive to hold and difficult to reposition. Most reuse proposals are capital-heavy: demolition, full conversion, or speculative tenant rebuild.

This proposal offers a different play:

- Low-to-moderate retrofit cost

- High public interest

- Strong PR value

- Community partnership with rescues

- Foot traffic to surrounding businesses (if any remain)

- A repeat-visitor model (memberships, regulars, volunteers)

- A recognizable identity: “the mall that became a sanctuary”

Developers don’t need to become animal experts. They can:

- lease space to a nonprofit/operator

- structure a revenue share

- or partner with municipalities seeking community-facing reuse

For cities, this is also a quality-of-life play:

- reduced feral colony pressure through structured intake

- improved adoption outcomes

- civic pride and tourism

Why this matters beyond cats

If this works, it changes how we think about “lower animals” and history.

Modern domestic life constantly erases nonhuman environmental memory. A mall-scale stable environment lets us ask:

- What happens when animals can build persistent worlds?

- Can stable “written” markers create faster assimilation for newcomers?

- Do place-based norms emerge when space stops resetting?

- Does welfare improve when an animal’s own records remain intact?

This is not about proving cats are little people. It’s about taking seriously that intelligence can be spatial, chemical, and historical, not only verbal.

And it’s about turning America’s commercial ruins into something unexpectedly humane.

What a pilot could look like (realistic scope)

A credible pilot does not require five malls. It requires one.

Phase 1: Secure a wing

- 50,000–150,000 sq ft

- Build the clinic, quarantine, staff areas

- Establish the three-layer zoning

- Begin intake and stabilization

Phase 2: Open limited public interface

- timed tickets

- café and lounge in a controlled zone

- strict quiet rules

Phase 3: Scale into additional wings

- expand retreat areas

- expand transitional corridors

- create additional observation nodes

If the pilot works, replication is straightforward because malls are standardized objects: corridors, anchor stores, storefront bays, loading docks. This is a repeatable template.

A closing note on intent

This proposal is not asking society to spend money on cats instead of people. It is asking society to solve multiple problems at once:

- reuse blighted property

- support overburdened urban rescues

- create a sustainable adoption pipeline

- fund non-invasive research that can improve animal welfare everywhere

- and build a destination that people genuinely want to visit

A dead mall is already a monument to human economic change.

It might also become the first place where domestic animals are allowed something we take for granted:

a stable world that remembers them.

Addendum

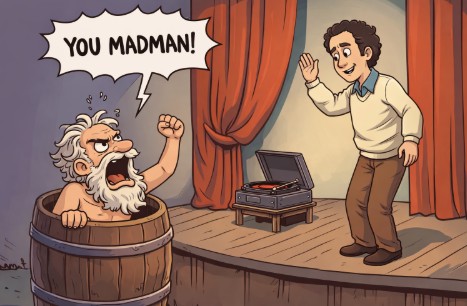

Naming the Flagship Deployment: The Shearer Center

Every serious idea has an origin moment — not a grant proposal or a white paper, but a small, ordinary observation that refuses to stay small.

This project’s catalyst was one of those moments.

In October, a casual social media post by cat lover Todd Shearer noted that after he threw away two well-used cat trees, his cats were visibly displeased — despite the fact that they still had two remaining. The tone was light, the complaint affectionate, the scenario familiar to anyone who has lived with cats.

What made the post matter was not the humor, but the implication.

The cats were not reacting to a lack of resources.

They were reacting to the loss of specific, marked, meaningful structures.

That observation — that cats respond not just to availability, but to the removal of accumulated history — sparked the question at the heart of this proposal:

What happens when we stop erasing the environmental records animals create, and instead allow them to persist, layer, and be read over time?

From that question came the theoretical exploration, the rescue-centered design, the non-invasive research model, and ultimately the idea of repurposing abandoned malls into stable, information-rich environments for domestic cats.

For that reason, this proposal formally recommends that the flagship deployment of the project be named:

The Shearer Center

A Feline Commons for Rescue, Research, and Urban Reuse

The name is not intended to elevate an individual as a benefactor or authority, but to acknowledge something more fundamental:

attentive observation by people who live with animals is often where real insight begins.

The Shearer Center stands as a reminder that:

- meaningful research can originate in everyday life,

- humor and seriousness are not opposites,

- and listening closely to how animals react to our choices can open entirely new lines of inquiry.

Future deployments may carry regional or functional names, but the first — the proof of concept — should honor the moment the question was first asked, not in a lab, but in a living room with two annoyed cats and two discarded cat trees.

Sometimes that’s how new ideas actually start.

Also, Todd is awesome.