This is an imagined monologue.

I’m borrowing a modern habit—comedians and entertainers sitting on talk shows, reminiscing about the greats, circling their influences with equal parts reverence and irritation—and giving it to someone who would never have been invited onto a couch.

Here, Diogenes of Sinope is allowed to speak about Andy Kaufman.

Not as an academic comparison.

Not as a clean lineage.

But as one disruptive figure recognizing another across time.

My admiration for both men is not polite, distant, or comfortable. It’s the kind of admiration that argues, needles, refuses reassurance, and leaves everyone involved a little uneasy. If Diogenes had encountered Andy Kaufman, it would not have been a handshake or a tribute. It would have been an exchange—intense, affectionate, abrasive, and unresolved.

That is the tone I’m aiming for.

What follows is not an explanation of Andy Kaufman’s work. It’s an attempt to imagine how someone who lived by exposure, refusal, and ethical discomfort might talk about a man who did the same thing on a stage, in a suit, with a microphone.

If it feels a little wrong to read, that’s appropriate.

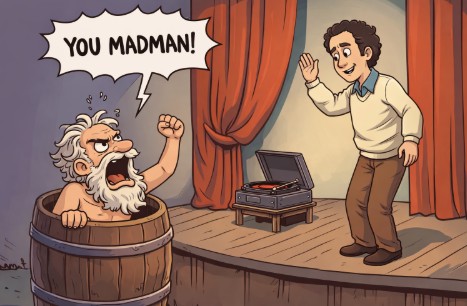

An Ode to Andy Kaufman, Written from the Barrel

I am Diogenes of Sinope.

I lived in a barrel, mocked kings, masturbated in public to make a point, and asked Alexander the Great to stop blocking my sunlight.

History calls me a philosopher.

My contemporaries called me a problem.

Andy Kaufman would have understood immediately.

He would not have asked what I meant. He would have asked how long I could keep doing it before someone broke character.

Andy Kaufman did not tell jokes. That framing is already a concession to comfort. He withheld resolution. He forced audiences to decide whether they were watching comedy, incompetence, cruelty, sincerity, or a trap. And then he refused to clarify.

That refusal is the work.

People still ask whether Andy was “in on it,” whether he was trolling, whether there was a deeper meaning. These questions miss the point in the same way people miss mine when they ask whether I really lived like a dog.

Of course I did. Of course he did.

Because the question was never what we were doing. The question was what you were willing to tolerate before you demanded reassurance.

Andy understood something modern people desperately try to forget: most social order is maintained by shared pretending.

Pretending that the show will end cleanly. Pretending that effort will be rewarded. Pretending that the performer is there to please you. Pretending that everyone agrees on what is happening.

I broke those pretenses by refusing clothes, property, or decorum. Andy broke them by refusing punchlines, sincerity, and relief.

Different methods. Same knife.

When Andy read The Great Gatsby on stage, page by page, for hours, it was not a prank. It was an experiment.

He was asking: How much boredom can you endure before you admit you came here for permission to feel something, not for truth?

When he wrestled women and leaned into hostility, it wasn’t misogyny or satire. It was exposure.

He was asking: How quickly will you justify cruelty if it arrives wrapped in entertainment?

When he played foreignness, awkwardness, or incompetence, he wasn’t mocking accents. He was forcing audiences to confront how thin their tolerance really was—how fast empathy collapses when convenience is threatened.

This is not comedy. This is ethical stress testing.

I carried a lantern in daylight looking for an honest man. Andy carried dead air, discomfort, and ambiguity into rooms full of people who paid to be told what to think.

Both of us discovered the same thing:

People will forgive almost anything except being denied the rules.

You can offend them. You can disgust them. You can insult them.

But if you refuse to tell them what this is, they will turn on you.

That is not an artistic problem. That is a civic one.

Andy Kaufman was a Cynic in the original sense—not bitter, not nihilistic, but unbuyable.

He could be rich or obscure, loved or hated, booked or banned, and none of it stuck. Because he never traded truth for stability. He never reassured the audience that the performance would return them safely to themselves.

I recognize that posture. It is the posture of someone who does not need approval to survive.

That is why Cynics end up homeless or rich and pass between the two without friction. Andy did the same. Fame slid off him the way wealth slid off me. Neither of us mistook attention for meaning.

People still argue about whether Andy was “really” funny.

That argument is the proof of success.

If the crowd cannot agree on whether you are serious, you have escaped classification. And classification is the leash. The moment they can name what you are, they can sell you, dismiss you, or bury you safely.

Andy never let them do that.

Neither did I.

I did not want followers. Andy did not want fans.

We wanted witnesses.

People who would go home unsettled—not because they were offended, but because something in the performance refused to lie down and behave.

Something that asked, quietly and without apology:

Why did you expect comfort? Who told you this was for you? What else are you pretending not to notice?

So this is my ode, from one Cynic to another.

You did not fail comedy. You exposed the audience.

You did not confuse people. You revealed how badly they needed clarity to feel safe.

You did not break the rules. You showed that the rules were already imaginary.

From my barrel to your stage: well done.

Now get out of the sunlight.

This piece isn’t meant to settle anything.

Like Andy’s work, and like Diogenes’ life, it resists being filed neatly under admiration, critique, philosophy, or comedy. It’s an act of recognition—one troublemaker noticing another and refusing to sand down the edges for the sake of clarity.

I don’t love either of these men because they were pleasant, correct, or easy to defend. I love them because they were uncompromising in ways that made people nervous, angry, and unsure of the rules they thought governed the room.

If the essay left you slightly uncomfortable, that’s not a flaw in the exercise. It’s the common ground between a philosopher who lived in a barrel and a performer who refused to let an audience relax.

Some exchanges aren’t meant to resolve.

They’re meant to linger.