The Culture of Separation

When people ask why working folks feel so tired now, I tell them it’s because we don’t just sell our labor anymore.

We sell our time.

And time is where people meet.

Time Was Once Shared

I grew up around long hours and hard work. My father worked the rails. There was nothing easy about it. But he came home. There was supper. There were Sundays. There were Saturdays that meant something.

People saw one another often enough to argue in the same rooms and make up before the week was out. You knew who was struggling. You knew who was cutting corners. You knew who could be trusted when it counted.

That kind of life didn’t make people soft.

It made them legible to one another.

And that matters more than we like to admit.

How the Day Got Longer

I don’t believe there was a moment when someone decided families were a problem that needed solving.

That’s not how these things usually move.

What does happen is that advantages get noticed.

Before anyone called themselves an industrialist, employers noticed that longer hours produced more output. When wars came, that lesson hardened. Wartime production doesn’t pause for dusk. It demands availability. It demands continuity.

Electricity made that possible.

Once work no longer depended on daylight, the night stopped being a boundary. And once continuous production proved useful, it stopped being temporary.

Systems rarely give back what they learn how to take.

What Had to Be Resisted

This is where labor history gets shortened into slogans.

The forty-hour week wasn’t a compromise born of goodwill. It was a line that had to be drawn because people understood what unlimited work actually costs.

Time off isn’t just rest.

It’s when people see one another without supervisors in the room.

If everyone is always working, but never together, comparison disappears. Conversation disappears. Collective memory disappears.

So labor fought for limits. Not because work was shameful, but because life without limits collapses inward.

For a while, those limits held.

How the Limits Were Eroded

Then productivity increased again — faster machines, better logistics, tighter systems.

And instead of shortening the day, we stretched it.

Availability became expectation.

Exhaustion became normal.

Schedules stopped lining up.

Weekends fragmented.

Work followed people home quietly, then openly.

Two incomes became necessary.

Community became optional.

Social life became something to schedule instead of something to inhabit.

This didn’t happen because people demanded it.

It happened because fragmentation doesn’t show up on a balance sheet as a cost.

Why Collaboration Feels So Hard Now

People talk about loneliness. About polarization. About the difficulty of cooperation.

I think we skip past a simpler explanation.

You can’t collaborate if you never overlap.

You can’t build trust if you never repeat encounters.

You can’t form culture if everyone is permanently occupied.

A person who is always working, always tired, always reachable is not free in any meaningful sense.

They may be paid.

But they are not available to one another.

That’s not a moral failure.

It’s a design outcome.

What the Math Actually Says

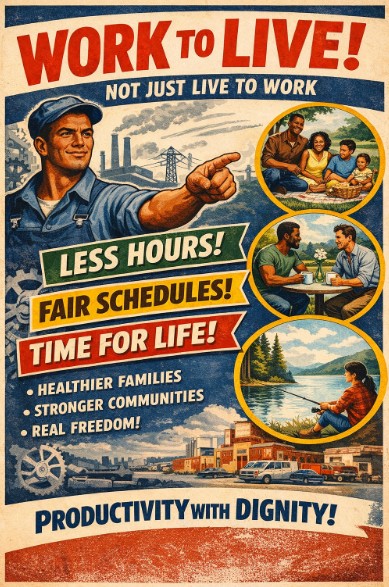

Given what modern productivity allows, a forty-hour week already asks too much.

If the goal were stable families, healthy communities, and people capable of thinking beyond the next obligation, the numbers would look different.

- Fewer hours

- Predictable schedules

- Shared days off

Not so people can avoid work — but so they can live alongside it.

Tranquility doesn’t come from idleness.

It comes from time that belongs to you and to others at the same time.

An Old Lesson We Keep Relearning

The fight for labor has always been a fight over time.

My father knew that.

A. Philip Randolph knew that.

Any good steward knows that.

Dignity doesn’t come from speed or availability.

It comes from having some control over the shape of your life.

When time is stripped down to utility, people stop gathering.

When people stop gathering, cooperation decays.

And when cooperation decays, everything else follows.

That’s where we are now.

Which means the problem isn’t mysterious.

And it isn’t new.

It’s just waiting for people who remember what time is actually for.

“A job that takes your whole life ain’t employment,” my father used to say.

“It’s conscription.”

Now you know, Jack.