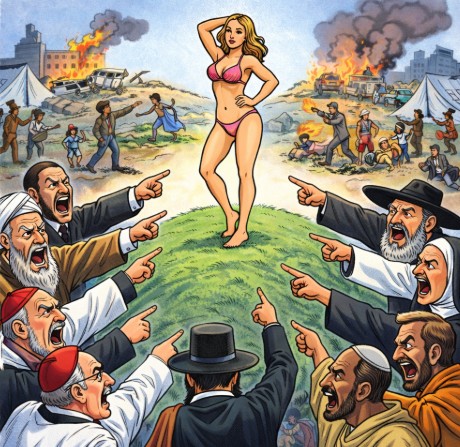

Modesty, Misplaced Anger, and the Strange Urge to Police the World

An essay on how modesty becomes corrupted when it turns outward—how conviction becomes control, and why real faith does not require enforcement.

If I believed—truly believed—that God did not want me to enjoy the pleasures of life; if I believed that the exposure of flesh was sinful, corrosive, or spiritually dangerous, I do not think it would be hard at all to understand the anger that animates religious fundamentalists.

In fact, I find that anger completely intelligible.

The modern Western world is loud, exposed, and unapologetic. Bodies are marketed. Desire is monetized. Intimacy is public performance. There are moments—plenty of them—where even someone like me, an old sailor with frankly lascivious tastes and a long history of enjoying life’s indulgences, finds himself blushing at what passes for normal public display.

So no, I don’t scoff at the feeling. I don’t dismiss it as ignorance or repression. If I believed that such exposure threatened my soul, I imagine I would feel something very close to rage.

But here is where I part ways.

I have a hard time believing that an all-powerful, all-knowing, eternal being would assign me the task of correcting everyone else’s behavior in Their name.

That assumption—that divine authority flows downward into personal enforcement—is where modesty stops being a spiritual discipline and becomes a weapon.

The Difference Between Conviction and Chauvinism

There is a profound difference between believing something is wrong for yourself and believing you are obligated to stop others from doing it.

Modesty, in nearly every religious tradition, begins as an inward practice. It is about restraint. About humility. About guarding one’s own heart, one’s own conduct, one’s own relationship with temptation and pride.

The moment modesty turns outward—when it becomes surveillance, condemnation, or coercion—it ceases to be modesty at all. It becomes chauvinism dressed up as righteousness.

And that transformation should give any serious believer pause.

If God is truly sovereign, truly omnipotent, truly capable of judgment and correction, why would They need me to act as an unpaid deputy? Why would the burden of universal moral enforcement fall on individual believers, many of whom are demonstrably struggling with the very temptations they claim to be fighting?

That logic doesn’t elevate faith.

It diminishes it.

Anger as a Signal, Not a License

If I felt anger rising in me at the sight of what I considered improper temptation, I would be inclined to treat that anger as information, not instruction.

I would ask myself:

- Why does this affect me so strongly?

- What desire or weakness is being exposed?

- Where am I failing to exercise restraint, discipline, or humility?

I would suspect—strongly—that the feeling was meant to direct my attention inward, not outward.

In that framing, anger is not a mandate to correct the world.

It is a reminder to correct the self.

Meditation, prayer, reflection, withdrawal—these are the traditional responses to temptation across religions, not confrontation and control. Salvation, where it is sought, is almost always described as personal work, not a crowd-control problem.

Which is why the modern obsession with public moral enforcement feels less like faith and more like anxiety displaced onto others.

Why I Don’t Think That’s What’s Happening

And yet, I don’t actually believe most fundamentalist anger comes from this place of introspection.

If it did, it would be quieter.

What we see instead is performative outrage, selective enforcement, and an overwhelming fixation on other people’s bodies, behaviors, and private lives—often paired with conspicuous silence about greed, cruelty, dishonesty, or abuse of power.

That pattern suggests something else is going on.

Not devotion, but fear.

Not modesty, but loss of control.

Not reverence, but status anxiety.

When people feel their cultural authority slipping, they often retreat into moral absolutism. Rules become stricter as influence wanes. The world must be forced to behave because persuasion no longer works.

That is not religion at its strongest.

That is religion under stress.

A Less Chauvinistic Reading

A less chauvinistic view of modesty accepts a hard truth: living in a pluralistic society means being exposed to values you do not share.

That exposure is not persecution.

It is coexistence.

You are free to dress modestly.

You are free to avert your eyes.

You are free to teach your children your values.

You are free to build communities that reflect your beliefs.

What you are not entitled to is universal compliance.

If your faith requires constant external enforcement to survive, the problem is not the world—it is the fragility of the belief system you are trying to protect.

Strong convictions do not need armies.

They need discipline.

The Power of Restraint

There is something deeply compelling about a person who lives their values without demanding that everyone else mirror them. Modesty practiced that way is not weak—it is formidable.

It says: I am responsible for myself.

It says: I trust my God enough not to play God.

It says: My salvation is not threatened by your freedom.

That posture does more to dignify faith than a thousand shouted condemnations ever could.

And if there is wisdom to be found in ancient traditions, I suspect it lies closer to that silence than to the noise we hear today.

But that’s just me.