Orcas, Signals, and the Problem of Being Understood

When two intelligent beings meet without a shared language, the greatest danger is not aggression.

It is misunderstanding.

This is something humans learned very early in their own history. Long before written language or formal diplomacy, our ancestors faced a recurring problem: how to approach unfamiliar groups without triggering violence. A sudden movement could be interpreted as an attack. A tool carried openly could be read as a weapon. Even silence could be dangerous.

Out of this uncertainty emerged one of humanity’s simplest and most enduring gestures: the open hand.

Anthropologists believe the greeting wave began as a visible demonstration of an empty hand — a way of showing that no weapon was being held, that the approach was intentional, and that restraint was being chosen. The gesture was inefficient, exaggerated, and unnecessary for survival. That was precisely the point. It demonstrated choice.

To wave was to say, without words:

I could act, but I am choosing not to.

This kind of signal only works in societies capable of recognizing intent. It is not about motion. It is about meaning.

Intelligence That Shows, Rather Than Takes

Across human cultures, similar gestures appear again and again. Salutes, raised hands, bows, ritual dress — each costs energy and serves no immediate survival function. They exist to manage uncertainty between minds.

Biologists and anthropologists call these non-utilitarian behaviors: actions that exist not to eat, flee, or reproduce, but to communicate something social and abstract. Their presence is one of the clearest markers of advanced cognition.

This is why jewelry, art, ritual, and fashion matter so much in human societies. They demonstrate that we are not merely reacting to our environment. We are choosing how to present ourselves within it.

For a long time, humans assumed this capacity was uniquely their own.

But the oceans tell a different story.

Orcas as Cultural Beings

Orcas, or killer whales (Orcinus orca), are not simply apex predators. They are among the most socially complex animals on Earth. Pods remain stable across generations. Hunting strategies differ between groups and are taught, not instinctive. Vocal dialects vary by pod, functioning much like regional accents. Adults actively train younger members.

In biological terms, this places orcas in a very small category: animals with culture.

Culture means behavior that is learned, shared, transmitted, and changed over time.

It means memory.

It means teaching.

It means identity.

Once this is understood, certain orca behaviors that once seemed trivial or puzzling begin to take on new significance.

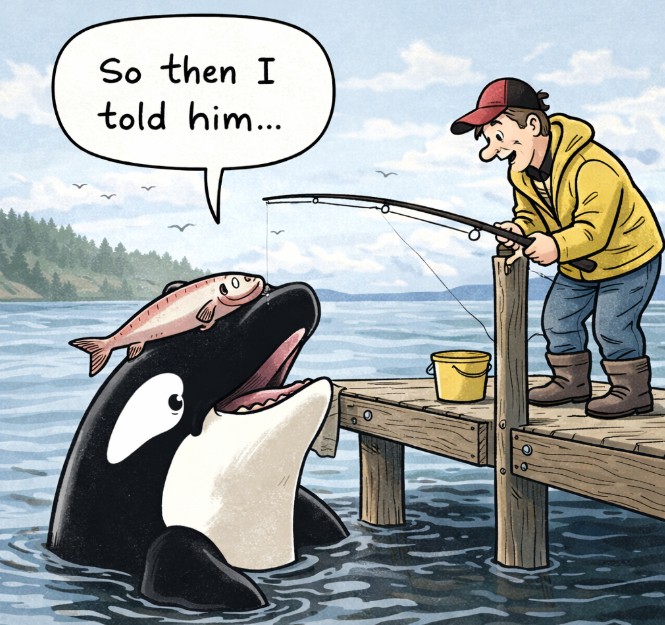

The Salmon on the Head

For a period of time, researchers observed orcas swimming with dead salmon balanced carefully on their heads. The behavior spread socially, appeared in multiple individuals, and then faded away.

It did not help them eat.

It did not help them hunt.

It did not help them survive.

From a purely biological standpoint, it made no sense.

From a cultural standpoint, it made perfect sense.

The behavior was conspicuous. It required planning. It served no practical function. It existed because others were doing it. In human terms, we would recognize this instantly as fashion, ritual, or performative behavior — something done to be seen, shared, and mirrored.

No one argues that the salmon “meant” something specific. What matters is that the behavior existed at all. It demonstrated that orcas can engage in shared actions chosen for reasons beyond survival.

That is not instinct.

That is culture.

Encounters With Boats

In recent years, another category of orca behavior has captured global attention: coordinated interactions with boats, particularly yachts. Certain pods have repeatedly approached vessels, targeted rudders, disabled steering, and then disengaged.

These actions are not random. They are learned, socially transmitted, and highly specific. The orcas do not sink boats indiscriminately. They do not attack humans. They focus on a single functional component and then stop.

In animal behavior, restraint is as important as aggression. An animal that could do more damage but does not is demonstrating control.

Control implies understanding.

Whatever the origin of these interactions — curiosity, play, negative experience — the pattern itself shows intentionality.

Two Ways to Respond to an Unknown Intelligence

Now we can begin a thought experiment.

Imagine a species that lives alongside humans for generations. It observes our coordinated behavior, our tools, our communication, our capacity for harm. It also lacks a shared language with us.

There are many possible responses to this situation.

One is defensive: disable the unfamiliar object, neutralize potential threat.

Another is expressive: demonstrate cognition without escalation.

These responses do not require planning at the level of a species. They emerge naturally within cultures. Human societies do this constantly — some groups respond to uncertainty with force, others with signaling and ritual.

Orcas, as cultural beings, may be no different.

Signaling Without Language

When language is unavailable, intelligence has only one reliable way to make itself known: through choice.

A behavior that:

- costs energy

- serves no survival purpose

- is shared socially

- is visible to others

…communicates something fundamental:

This action is intentional.

Biologists call such actions ostensive behaviors — behaviors performed to be noticed as deliberate.

The human wave is one.

Ritual dress is another.

Art is another.

So is an orca wearing a fish on its head.

Seen this way, symbolic excess is not meaningless. It is one of the safest ways for an intelligent being to say:

I am more than instinct.

Why Humans Struggle to See It

Humans tend to recognize intelligence when it looks like us: tools, construction, numbers, speech.

We are less comfortable recognizing it in play, ritual, or non-productive behavior — even though those are the very things we value most in ourselves.

So we laugh at the salmon.

We fear the rudder.

We separate the behaviors instead of asking what they have in common.

What they share is restraint, culture, and the capacity to act outside necessity.

A Careful Conclusion

This is not a claim that orcas are trying to speak to us.

It is not a story about hidden councils or deliberate interspecies diplomacy.

It is a quieter suggestion.

If a species demonstrates culture, memory, restraint, and symbolic behavior, then some of its actions may function not as instinct or anomaly, but as expressions of mind — visible only if we are willing to recognize them as such.

Jane Goodall once urged us to watch first, interpret later, and resist the urge to reduce complex beings to simple explanations.

The oceans may be asking us to do the same.

Because when intelligence cannot speak, it does not disappear.

It performs.