Johnstown, Pennsylvania. Cambria County

Johnstown is not broken.

It is under-populated.

That distinction matters, because it changes what the problem is—and therefore what the solution can be.

Economically, Johnstown is weak. That’s not controversial. The business climate looks like most small to mid-sized American cities: a handful of established groups doing what they can, a local government wrestling with limited resources, and a civic ecosystem that mostly knows how to maintain what exists rather than invent what comes next.

None of that is unique. None of that is fatal.

What is unusual is what Johnstown already has.

The Greater Johnstown Area has roughly 132,000 people. Johnstown proper has about 20,000. That is not the density of a city. It’s barely the density of a small town—spread across city-scale infrastructure, neighborhoods, schools, parks, roads, utilities, and institutions built for far more people than currently live here.

The missing resource isn’t capital.

It isn’t land.

It isn’t water, energy, or location.

The missing resource is people.

And not just any people—people whose skills are now mobile, whose work is no longer tied to a single office tower or metro core, and who are increasingly aware that the places they live are extracting more from them than they give back.

That’s the context in which the forest city makes sense.

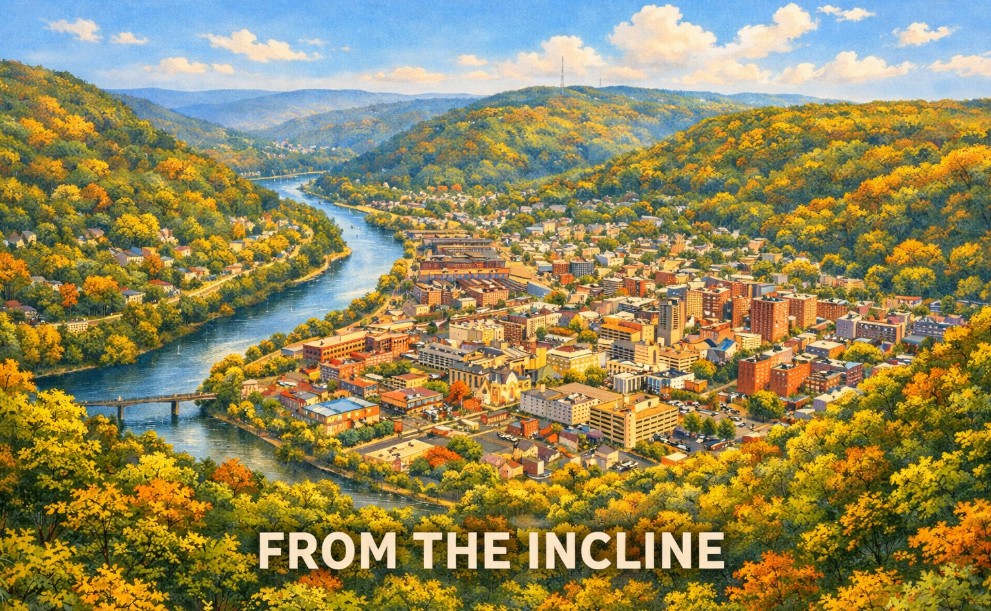

Johnstown sits in a bowl of mountains and rivers. It has four real seasons. Forested hills wrap around neighborhoods that were once dense with labor and life. The natural world never left here—it simply waited. Trees, water, soil, shade, quiet, scale. These are not lifestyle amenities anymore. They are structural advantages.

The forest city is not a metaphor about being quaint or sleepy. It’s a systems description.

Forests work because they are:

- distributed, not centralized

- cooperative rather than extractive

- resilient through redundancy

- capable of regrowth after disturbance

Healthy towns work the same way.

Johnstown already has the bones of a forest city: space to grow without sprawl, real estate that allows experimentation, schools that can scale with enrollment, and a cultural memory of work that builds things. What it lacks is the density of human energy needed to reactivate those systems.

And that’s where the moment we’re in matters.

We are living through the first period in history where large numbers of highly skilled people can choose where they live independently of how they work. At the same time, the cost of staying in legacy “successful” cities has become punitive—financially, psychologically, and socially.

People are tired of paying more for less.

Johnstown offers something rare: a place where effort still compounds locally. Where buying a house isn’t an act of financial submission. Where starting something doesn’t require permission from five layers of rent-seeking intermediaries. Where a community can still notice when you show up and contribute.

The forest city isn’t about erasing Johnstown’s industrial past. It’s about understanding that the next phase of prosperity doesn’t come from extraction—it comes from regeneration. From bringing people back into a system that already knows how to support them.

This isn’t a call for mass migration or overnight transformation. It’s a recognition that even modest inflows—dozens, then hundreds of skilled, engaged people—change the math. Schools stabilize. Small businesses diversify. Civic life thickens. Culture returns not as nostalgia, but as participation.

The forest city grows quietly. It doesn’t announce itself. It becomes obvious over time.

Johnstown doesn’t need to be reinvented. It needs to be re-inhabited.

And for people looking for a place where their work, their neighbors, and their environment can actually connect—Johnstown, the forest city, is already here, waiting to grow back into itself.