Letter on Capitalism, Necessity, and the Line We Need to Draw

Capitalism is a good engine.

It is not a good religion.

This distinction matters, because much of our modern confusion comes from treating a tool as a theology. We defend markets where they work best, and then keep defending them long after they’ve wandered into places they were never meant to go.

Myself included.

I believe — still — that capitalism drives innovation better than any alternative we’ve yet devised. It rewards risk, punishes complacency, and scales ideas faster than committees ever could. Most of the comforts we take for granted arrived not through decree, but through competition.

But engines have operating ranges. Push them beyond design, and they don’t just perform poorly — they become destructive.

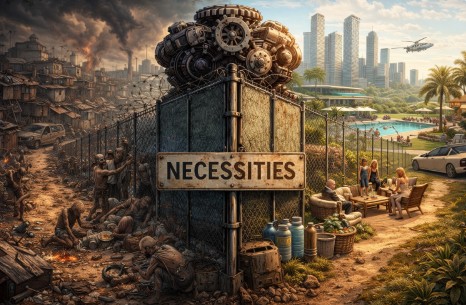

The trouble began when we stopped distinguishing between utilities and luxuries.

In a healthy system, capitalism thrives on choice. You can buy this phone or that one. Eat here or there. Subscribe or cancel. The freedom to walk away is what disciplines the seller. It is the quiet regulator markets rely on.

But that freedom evaporates the moment a good becomes a necessity.

Food.

Water.

Shelter.

Energy.

Basic mobility.

Healthcare.

Not because I say so. Because the law does.

When participation is mandatory — either directly or functionally — the social contract changes.

A luxury is something you desire.

A utility is something you cannot reasonably refuse.

There is, of course, room for honest debate around the edges.

Reasonable people can disagree about where necessity ends and luxury begins. Is high-speed internet essential everywhere, or only in some places? Is personal transportation a necessity, or a regional convenience shaped by design choices we’ve already made? Those are legitimate arguments, and a healthy society should expect to keep having them.

But the existence of edge cases does not erase the center.

Some things are not ambiguous. Some goods become non-optional not by personal preference, but by legal, economic, or infrastructural design. When opting out is no longer realistic, the question is no longer taste or ideology — it is obligation.

And here is the line we need to draw:

It is legitimate to extract profit from desire.

It is corrosive to extract profit from necessity.

The moment the state declares something essential — either by mandate or by making modern life impossible without it — it inherits responsibility for how that thing is provided.

This is not socialism.

It is stewardship.

Capitalism remains the best system for innovation precisely because it is ruthless about failure. But necessity cannot be allowed to fail in the same way a gadget or service can. You cannot “disrupt” insulin. You cannot beta-test clean water. You cannot tell a person in crisis to wait for version 2.0.

So the question is not whether markets belong here.

It is how tightly the fence must be built.

I find myself returning to a simple framework — one that would have spared us a great deal of shouting if we had adopted it earlier.

Anything broadly deemed a necessity by law and function — not merely by opinion — must fall into one of two categories:

First:

It is provided directly by the people, for the people, at cost.

Public utilities, transparently managed, boring by design, and accountable to voters rather than shareholders.

Second:

It is provided through open markets, but under strict rules.

Standardized billing.

Capped margins.

Full transparency.

Congressional oversight with real teeth.

No dark pricing. No extraction through complexity. No profit by confusion.

This preserves innovation where it matters — delivery, efficiency, technology — without allowing rent-seeking at the point of human vulnerability.

Everything else?

Everything nonessential?

Let capitalism off the leash.

Let luxury markets run. Let companies compete, fail, reinvent, and chase profit as hard as they like. Let desire remain the proving ground of ideas. That is where capitalism shines, and where it should be defended without apology.

The balance we’ve lost is not between left and right.

It is between choice and compulsion.

We allowed profit to follow compulsion, and then acted surprised when trust collapsed.

The healthcare debate — yes, that one — becomes less radioactive when framed this way. The problem was never markets. It was forcing participation without enforcing responsibility. Mandates without ownership. Payment without agency. Oversight that arrived after the invoice.

That arrangement violates the social contract.

The only reason we participate in society at all is to make life safer, healthier, and more stable together. When the structures meant to protect that compact begin extracting from it instead, people feel it instinctively — even if they lack the language to explain why.

Capitalism should reward invention, not inevitability.

Profit should follow value creation, not human need held hostage.

This is not an argument against markets.

It is an argument for putting them back where they belong.

A republic that cannot distinguish between utilities and luxuries will eventually commodify everything — and then wonder why nothing feels shared anymore.

Grammina would have said it more simply:

“You can charge for the extras.

But you don’t put a tollbooth on the bridge everyone has to cross.”

That, I suspect, is where a mature society lands.