On Hair, Evolution, and Why Bad Comparisons Keep Failing

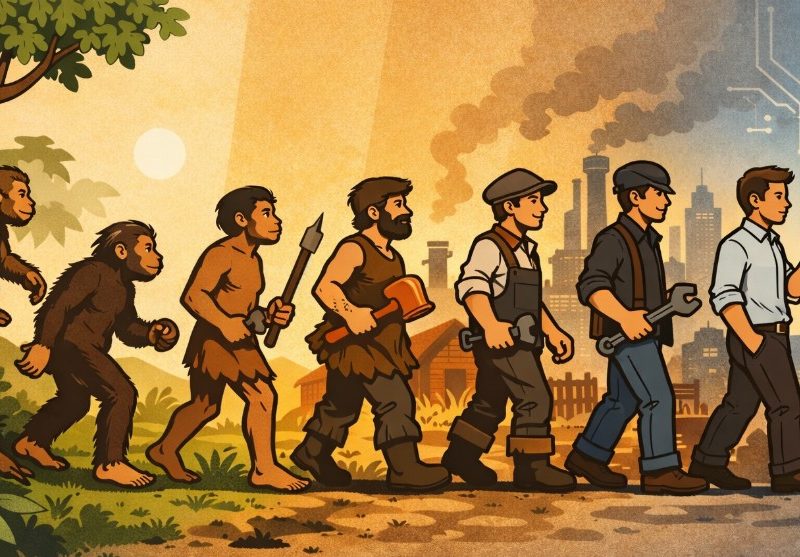

I was working on Iron Age material and putting together a visual with Brobot—one of those familiar evolutionary progressions meant to make material transitions obvious. Stone. Copper. Iron. Industry. The usual shorthand.

While reviewing the image, I did something I now do almost automatically: I scanned it for any hint of unintended bias or lazy symbolism. Not because I’m particularly delicate, but because the internet is currently saturated with some genuinely racist nonsense—especially videos trying to compare individual humans to apes as a form of insult or hierarchy.

This is not that. And before going any further, let me be explicit:

If you believe some humans are “closer to apes” than others in any moral or biological sense, you are misunderstanding both biology and history so badly that you should probably have someone read the rest of this to you slowly.

What caught my attention wasn’t a comparison between people. It was something subtler.

In the evolutionary image, every figure—from early hominins through modern humans—had straight hair all the way back. That wasn’t intentional. It was just default illustration shorthand. But it made me stop and think.

Why is tightly kinked scalp hair absent from every primate except modern humans?

And why does it appear only after a very specific sequence of evolutionary events?

That question turns out to be more interesting—and more clarifying—than most people realize.

Hair is not fur, and that distinction matters

Non-human primates don’t have “hairstyles.” They have fur.

Their hair:

- covers most of the body,

- grows in relatively uniform patterns,

- and serves insulation more than thermal regulation.

Humans are different. At some point in our evolutionary history, we lost most of our body fur. That loss is one of the defining features of the human lineage. It enabled endurance running, improved heat dissipation, and fundamentally changed how we interacted with hot environments.

Crucially, we retained hair primarily on the scalp.

That means human scalp hair is not just “ape hair with culture added.” It is a specialized structure that evolved after fur loss.

This is the first constraint.

Tightly kinked hair could only evolve after fur loss

Tightly kinked (“woolly”) scalp hair has very specific properties:

- The hair shaft is flattened and elliptical.

- The curl pattern is irregular and tight.

- The structure promotes airflow above the scalp while shading it from direct solar radiation.

This only makes sense on a mostly hairless body in high heat and high UV environments.

You cannot get this trait:

- in a fully furred primate,

- on a body that hasn’t already lost fur,

- or before long-term exposure to intense equatorial conditions.

That immediately tells us something important:

Tightly kinked scalp hair is a derived, late-arising human trait.

It does not represent a “primitive” condition. It represents additional specialization layered on top of earlier human adaptations.

Why it doesn’t appear everywhere

As humans dispersed out of Africa, selective pressures changed.

In regions with:

- lower UV,

- cooler climates,

- seasonal cold stress,

the intense selection for extreme scalp heat management relaxed. Hair forms diversified through drift and local adaptation—straight, wavy, loosely curly—without the same pressure to maintain tight kinking.

This does not mean one group stopped evolving while another continued. All populations evolved continuously.

It means different traits were being selected for, or not selected against, depending on environment.

This is the same evolutionary logic that explains:

- lactose tolerance in some populations,

- high-altitude blood chemistry in others,

- Arctic fat metabolism,

- or sickle-cell traits in malaria zones.

No hierarchy. No ladder. Just tuning.

And here’s the part people keep getting exactly backwards

No other primate—chimpanzees, gorillas, orangutans, monkeys of any kind—has tightly kinked hair.

None.

Which leads to an uncomfortable but unavoidable conclusion for people who insist on oversimplifying evolution:

If you were foolish enough to measure “distance from apes” by the presence of uniquely human derived traits, then tightly kinked scalp hair places a population further away from non-human primates, not closer.

That is not a value judgment.

It is not a ranking.

It is simply how derived traits work.

The mistake is thinking evolution is about “higher” and “lower” at all.

The real lesson (and why this mirrors the metal ages)

Evolution—biological or technological—does not move toward a goal. It responds to pressure.

When pressure stays high, traits intensify.

When pressure relaxes, traits stabilize or diversify.

That’s true of:

- hair,

- skin pigmentation,

- metabolism,

- metallurgy,

- economies,

- institutions.

Copper didn’t replace stone because it was morally better.

Iron didn’t replace copper because ironworkers were superior people.

Systems changed. Pressures shifted. Adaptations followed.

And every time we forget that—and try to rank outcomes instead of understanding contexts—we repeat the same category error.

That error has caused enough damage already.

We don’t need to run that experiment again.