The First four thought experiments in this chain.

Before we go any further, here’s a brief recap of how this thought experiment started—and how we arrived here.

The Series So Far

Part I — Did the USA Just Elect an Emperor?

A historical and geopolitical analysis asking whether American imperial drift was even theoretically possible.

https://blueribbonteam.com/blog/2025/01/21/did-the-usa-just-elect-an-emperor/

Part II — Did the USA Just Elect an Emperor? (Revisited)

A reassessment after new developments—Panama Canal chatter, corporate-government fusion, and rising continental tension.

https://blueribbonteam.com/blog/2025/03/14/did-the-usa-just-elect-an-emperor-revisited/

Part III — What If It Was Popular?

A pivot from authoritarian drift to a voluntary, democratic, citizen-led unification of North America.

https://blueribbonteam.com/blog/2025/03/17/what-if-it-was-popular/

Part IV — USNA: Keeps Drawing Me In

The first draft of a possible continental constitution and political architecture.

https://blueribbonteam.com/blog/2025/03/18/usna-keeps-drawing-me-in/

Now, in Part V, we finally address the question every serious proposal must answer:

If a continental republic is even theoretically possible… where should its capital be?

Washington can’t be the capital.

Ottawa can’t be the capital.

Mexico City can’t be the capital.

Any existing capital would make unification look like annexation.

A new republic demands a new center.

And the only place that answers history, geography, and legitimacy at the same time is Four Corners.

Not as a novelty.

Not as a roadside attraction.

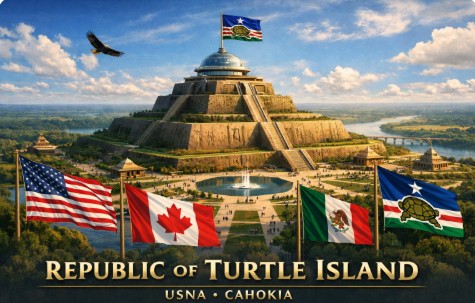

But because of what it symbolizes—especially under the umbrella concept of the Republic of Turtle Island.

The Center of Turtle Island

Four Corners sits at the convergence of:

- The Navajo Nation

- The Ute Mountain Ute Reservation

- Hopi and Zuni homelands

- Multiple overlapping Indigenous cultural histories

If the first peoples of this continent are to have a true structural and constitutional presence in a new federation—not a token role, not advisory, not ceremonial—then placing the capital here makes that commitment literal.

A capital at Four Corners sends a message stronger than any clause in a constitution:

“This republic begins with those who were here first.”

It is the only location that makes Indigenous participation a foundational pillar, rather than a political afterthought.

A Neutral Capital for a Neutral Beginning

Choosing Four Corners also resolves the most explosive political problem of unification:

No nation gets to place its old capital at the top of the new power structure.

- Washington → looks like U.S. takeover

- Ottawa → looks like Canadian takeover

- Mexico City → looks like Mexican dominance

- Any major city → creates immediate imbalance and resentment

Four Corners is:

- not a current capital

- not a megacity

- not the heart of any existing national bureaucracy

- not tied to colonial power structures

- geographically central

- politically neutral

- symbolically clean

It offends no major power—and honors those most historically ignored.

A Purpose-Built Capital for a Purpose-Built Republic

Locating the capital at Four Corners allows a planned civic district to be built from the ground up:

- Sustainable desert architecture

- Solar-first energy systems

- Walkable, human-scale design

- Closed-loop water recycling infrastructure

- Indigenous-informed planning principles

- A diplomatic campus for all founding nations

- A tricameral legislature designed for visibility and access

- No inherited elite districts or entrenched bureaucracies

Naming the city is the business of the elected representatives of the new republic—not this article, and not any individual.

But anchoring it at Four Corners gives the naming process meaning, legitimacy, and unity.

A Republic Facing the Century Instead of the Past

Let’s be explicit:

This is not a call for rebellion, secession, or unilateral expansion.

It is a call for governments to explore a deliberate, voluntary, lawful transition into a continental federation—led by elected officials, ratified by citizens, and negotiated openly.

A republic with a capital at Four Corners would:

- Acknowledge Indigenous nations as foundational partners

- Neutralize historical rivalries

- Prevent any single nation from inheriting dominance

- Set a symbolic tone of unity and balance

- Align with the continent’s real population and economic gravity

- Begin on uncontested civic ground

It is a constitutional blank slate in the most literal sense.

The Invitation

Part V asks the governments of North America to consider—openly and peaceably—the creation of a new continental republic whose capital sits at the continent’s shared center.

A republic:

- not imposed by force

- not welded together by fear

- not anchored in old capitals or old hierarchies

But one that begins at the exact center of Turtle Island—where four lands meet and the first peoples walk.

A republic built from the middle outward.

A republic that begins at the beginning.

Afterthoughts

On Origins, Intent, and Cycles

This thought experiment began in a very specific moment.

The early posture of the current presidential term felt unusually aggressive—not just in language, but in the direction of power itself. Executive reach, foreign signaling, and institutional pressure created the conditions for a simple question:

If systems drift, what other systems are even conceivable?

What followed was not advocacy or instruction.

It was not a proposal or a plan.

It was the result of playing with an idea long enough to see its shape.

Nothing more.

No calls to action.

No prescriptions.

No claim of inevitability.

Just the act of thinking something through instead of reacting to it.

After sitting with the idea longer—and after doing something unfashionable but necessary: staring at a map for a while—the center shifted.

Cahokia is the better choice.

Not because it is convenient.

Not because it is symbolic in the abstract.

But because it already was.

Cahokia stood at the confluence of rivers—the original circulatory system of the continent. It was a place of trade, governance, density, and culture at continental scale long before modern borders, and long before modern capitals imagined permanence as a virtue.

Cahokia does not represent dominance or conquest.

It represents arrival, organization, and return.

It rose.

It complexified.

It declined.

And it gave itself back to the land.

Not as failure—but as cycle.

That cyclical understanding matters. Civilizations are not ladders. They are systems with seasons. Growth, complexity, contraction, and renewal are not endpoints; they are rhythms.

Cahokia feels less imposed.

Less theoretical.

More grounded.

More… right.

That revision itself is part of the exercise. Ideas are supposed to change when given time, restraint, and context.

And that, ultimately, is all this ever was.